PLAZA PARQUE LUIS BARRAGAN

Located in the iconic neighborhood of El Pedregal in southern Mexico City, Pabellón Pedregal emerges as a thoughtful response to the evolution—and challenges—of a historically significant urban fabric. El Pedregal was originally conceived in the 1940s as a modernist residential enclave, part of a visionary master plan led by Mexico’s only Pritzker Prize laureate, Luis Barragán. Designed atop the dramatic volcanic landscape of El Pedregal de San Ángel, the neighborhood quickly became a testing ground for the ideas of modern architecture, housing a generation of experimental and expressive residential works.

Over time, the neighborhood evolved into a mixed-use district, incorporating schools, parks, restaurants, retail corridors, and informal commercial conversions of residential properties. As demand for space continued to grow—both from residents and businesses—many of the original single-family homes along major arteries such as Avenida de Las Fuentes were transformed into small commercial plazas. Unfortunately, this transformation often neglected the urban environment, resulting in introverted retail spaces that offered little to no contribution to the public realm.

Our project was located directly across from Luis Barragán Park, one of the most emblematic and underutilized public spaces in the neighborhood. Observing the park’s deteriorated condition and lack of active engagement, we saw an opportunity to reimagine the commercial plaza typology—not as a closed box, but as a catalyst for community life and public space revitalization.

Instead of filling the site edge-to-edge, we strategically pulled back the building’s central façade, carving out a semi-public courtyard that serves as an open invitation for the neighborhood to enter and gather. This central space becomes a continuation of the street and a visual extension of the park, blurring the lines between commerce and community. The plaza is not only a commercial hub—it becomes a stage for daily life.

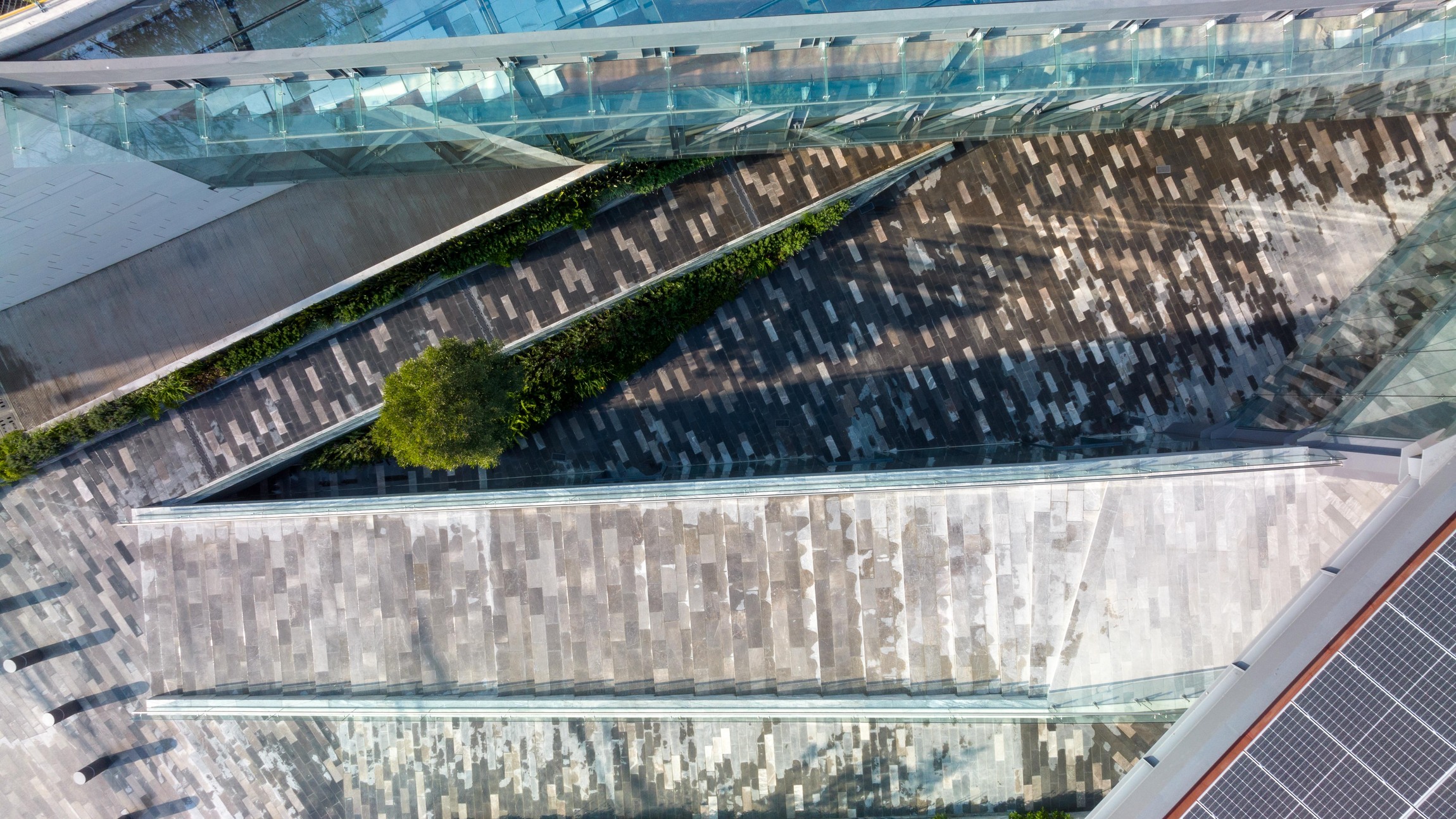

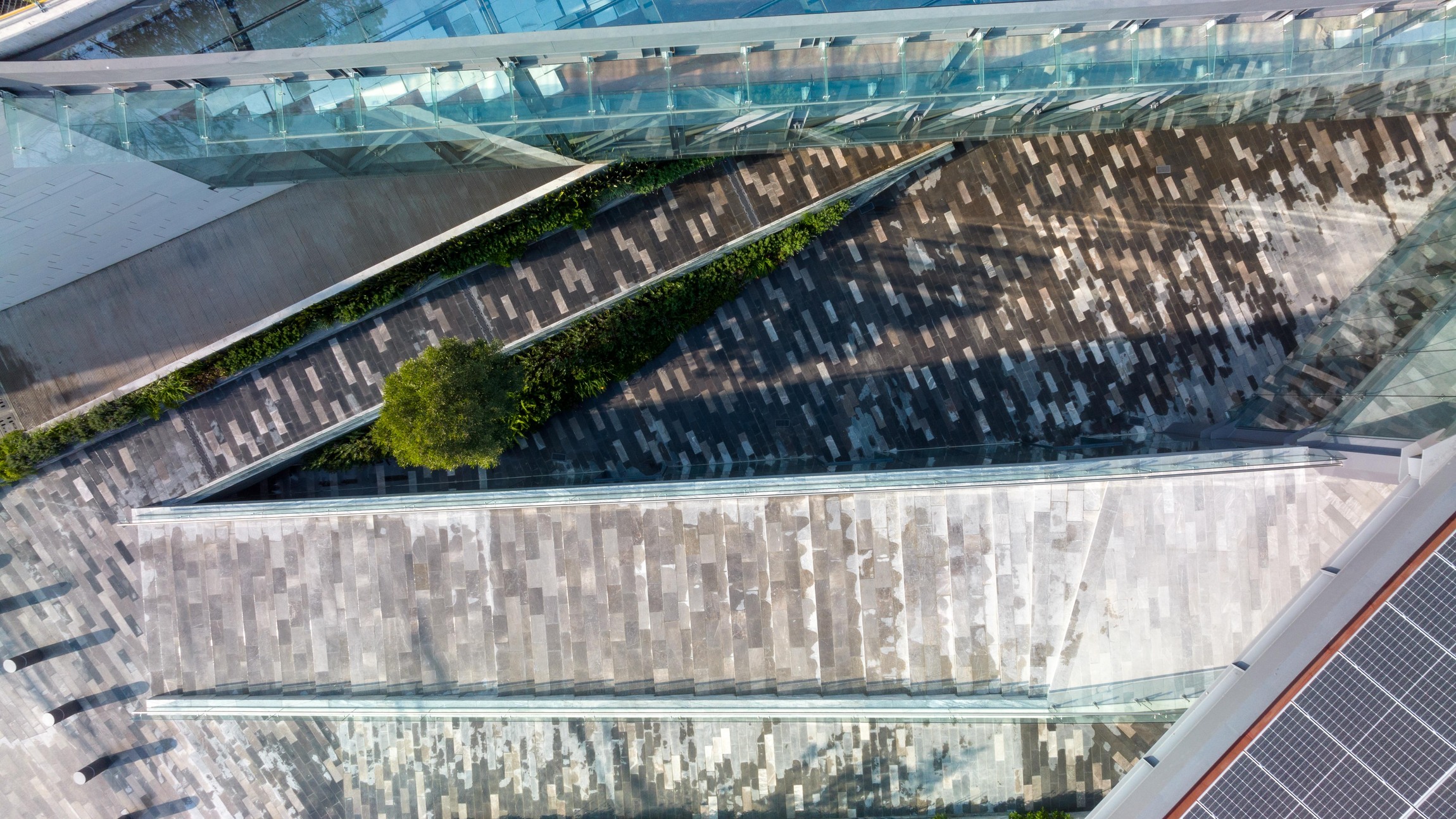

Architecturally, the building is articulated through a series of ramps and terraced levels, making the entire site accessible and walkable. At the heart of the composition is a large central stair, which also functions as an amphitheater, facing the park. In this way, the park becomes the main protagonist—a living stage for informal performances, children’s play, or moments of pause. This staircase transforms into seating for watching the natural world or the neighborhood unfold before your eyes.

The design of Pabellón Pedregal is guided by a core intention: to create architecture that gives back to the city, enhancing the pedestrian experience and activating forgotten public spaces. It avoids the insular nature of typical commercial plazas, and instead proposes a built environment where architecture and landscape, culture and commerce, history and future, all come together in dialogue.

In the spirit of Barragán himself, the project is quiet yet powerful, restrained in form but generous in gesture—an architecture that does not impose, but rather invites.

PLAZA PARQUE LUIS BARRAGAN

Located in the iconic neighborhood of El Pedregal in southern Mexico City, Pabellón Pedregal emerges as a thoughtful response to the evolution—and challenges—of a historically significant urban fabric. El Pedregal was originally conceived in the 1940s as a modernist residential enclave, part of a visionary master plan led by Mexico’s only Pritzker Prize laureate, Luis Barragán. Designed atop the dramatic volcanic landscape of El Pedregal de San Ángel, the neighborhood quickly became a testing ground for the ideas of modern architecture, housing a generation of experimental and expressive residential works.

Over time, the neighborhood evolved into a mixed-use district, incorporating schools, parks, restaurants, retail corridors, and informal commercial conversions of residential properties. As demand for space continued to grow—both from residents and businesses—many of the original single-family homes along major arteries such as Avenida de Las Fuentes were transformed into small commercial plazas. Unfortunately, this transformation often neglected the urban environment, resulting in introverted retail spaces that offered little to no contribution to the public realm.

Our project was located directly across from Luis Barragán Park, one of the most emblematic and underutilized public spaces in the neighborhood. Observing the park’s deteriorated condition and lack of active engagement, we saw an opportunity to reimagine the commercial plaza typology—not as a closed box, but as a catalyst for community life and public space revitalization.

Instead of filling the site edge-to-edge, we strategically pulled back the building’s central façade, carving out a semi-public courtyard that serves as an open invitation for the neighborhood to enter and gather. This central space becomes a continuation of the street and a visual extension of the park, blurring the lines between commerce and community. The plaza is not only a commercial hub—it becomes a stage for daily life.

Architecturally, the building is articulated through a series of ramps and terraced levels, making the entire site accessible and walkable. At the heart of the composition is a large central stair, which also functions as an amphitheater, facing the park. In this way, the park becomes the main protagonist—a living stage for informal performances, children’s play, or moments of pause. This staircase transforms into seating for watching the natural world or the neighborhood unfold before your eyes.

The design of Pabellón Pedregal is guided by a core intention: to create architecture that gives back to the city, enhancing the pedestrian experience and activating forgotten public spaces. It avoids the insular nature of typical commercial plazas, and instead proposes a built environment where architecture and landscape, culture and commerce, history and future, all come together in dialogue.

In the spirit of Barragán himself, the project is quiet yet powerful, restrained in form but generous in gesture—an architecture that does not impose, but rather invites.